Given the level of opportunism occurring in the Australian Vocational Education & Training higher education sector since deregulation (uncapping places & fees), recent articles:

- ‘Reforming vocational education: it’s time to end the exploitation of vulnerable people’

- ‘$1.2bn VET FEE-HELP loans ‘may not be repaid’’

I think it is worth reblogging my Senate submission (Feb 2015) suggesting a new incentive compatible model for a deregulated higher education market where education providers have ‘skin in the game’. This Senate submission provided a solution to what I saw as a fundamental misunderstanding of the risks associated with deregulating higher education within the current policy framework, published as an opinion piece in The Australian (Oct 2014):

This was followed up by an article calling for universities to have more ‘skin in the game’ (Mar 2015):

I presented this model at the ANU Forum on Higher Education Financing, Friday 13th August 2015, on the topic ‘Should universities have skin in the game?’.

This model can be applied to any type of higher education provider where students have access to government administered income-contingent loans. Whether providers be universities, vocational, professional bodies or dedicated postgraduate institutions. This model can even be applied to specific types of courses which are regulated separately, such as proposed Australian university flagship courses.

——————————————

Originally presented at the ANU Forum on Higher Education Financing, 13th August 2015, on the topic ‘Should universities have skin in the game?’ based on my Senate submission Feb 2015.

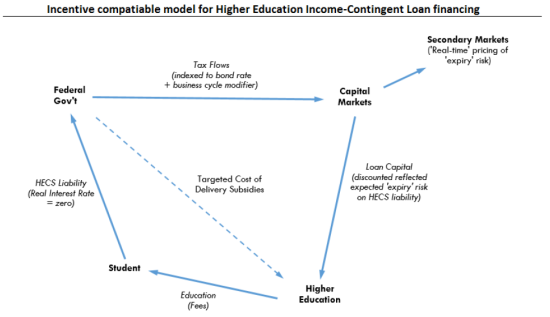

The purpose is to suggest a model which combines the social equity benefits of income-contingent loans with a market design that is ‘incentive compatible’ through an appropriate price discovery mechanism.

Executive Summary

Key objective of this model is to create an ‘incentive compatible’ nexus between the ‘expiry risk’ of student loans and quality of education at the education provider level.

Requiring education providers to have ‘skin in the game’ addresses the following types of adverse provider behaviour :

1) over-servicing (‘moral hazard’),

2) exploitation of ‘experience good’ information asymmetries where quality can only be assessed after purchase, and

3) taking advantage of ‘Veblen good’ effects where increasing price increases demand due to education being a ‘positional good’.

Additionally:

- Social objectives of income-contingent loans will remain intact. From a student perspective there are no changes.

- The fundamental change is that Higher Education providers will receive student fee revenue from capital markets (e.g. fund managers) instead of from government.

- Capital markets receive the future student loan liability repayments linked to the Higher Education provider funding.

- Fund managers will pay the Higher Education providers the nominal value of the loan liability less amount to cover the ‘expiry risk’ of (some) loans not being repaid.

- Higher Education providers thereby bear the risks associated with the level of fees charged and the quality of education delivered.

- Price increases at the expense of quality is resolved via a costly-signalling mechanism where capital markets have a strong incentive to reduce expiry risk on student loans funded by debt pooled by a Higher Education provider.

- Critically, the two market participants best able to resolve the problems of uncertainty and information asymmetry, capital markets (fund managers) and Higher Education providers, bear most of the risk.

- Students bear no greater risk than they currently incur. An incentive compatible market should decrease risk.

- The model allows the Federal government to achieve social and economic objectives via specific subsidies such as tax credits for low SES students.

Introduction

Higher education in Australia is progressively moving towards a free-market approach in order to improve flexibility and diversity of choice. However, a free-market approach has important budgetary, quality and social equity implications that need to addressed. Any market oriented solution needs to meet both social equity and economic efficiency considerations.

There is a significant risk that a combination of Income-Contingent Loans with uncapped, deregulated free markets will lead to large increases in Higher Education fees for courses and/or a lowering of teaching quality – where the price paid for education is not reflected by underlying value. Paradoxically since opening up the Higher Education market to private providers and uncapping student places, prices have increased at the same time as the volume of students has increased. Between 2013 and 2014 prices increased 26% (CPI adjusted) and number of students has increased 263%. Clearly, increased competition hasn’t lead to lower prices. Quality has also suffered as we have seen a number of recent de-registrations.

Income-contingent loans are a form of government insurance subsidy which removes the wealth constraints from the decision making of disadvantaged students. Combining government subsidies and free-market dynamics without constraints will lead to increasing pressure on the Federal budget.

Currently, higher education providers are enjoying a substantial free-carry subsidy on the expiry risk of student loan liabilities they generate through course fees.

Any deregulation of higher education should address both market and social objectives.

The social objectives of higher education deregulation are:

- Equity: all members of society are able to participate on an equal footing with all other members of society independent from constraints of wealth.

- Opportunity: uncertainty about the future should not constrain educational choices.

- Cost efficiency: mechanisms to achieve equity and opportunity are cost efficient so as not to negate the benefits of reforms.

The market objectives of higher education deregulation are:

- There exists a ‘price signal’ that drives incentive compatible behaviour,

- A financial constraint that necessitates trade-offs between price and quality so that choice can be optimized.

- That transaction costs of any market mechanism be kept to a minimum.

Income-contingent loans achieve these social objectives. A free-market approach with flexible pricing of Higher Education fees achieves market objectives within a normal market. However, a market where debt is funded through government subsidized debt, income- contingent loans, is not a normal market. Income-contingent loans weaken the responsiveness of course fee levels as a price-signal and removes the financial constraints of wealth.

Importantly, income-contingent loans do achieve the third market criteria of low transaction costs suggesting the solution lies in finding the right price-signal and financial constraint in order to achieve compatibility between social and market objectives of deregulating higher education.

Problems of uncertainty & information asymmetry

Choices in education are complex. Economic returns from investing in education are realized over long time frames and subject to a large number of interacting variables. This leads to a high degree of uncertainty which requires a high level of expertise and resources to resolve meaningfully.

Different levels of information are held by various agents within the higher education sector, such as students and Higher Education providers, which leads to information asymmetry. Additionally, education is considered an ‘experience good’ because only after experiencing a Higher Education provider do students understand how well the education experience suits their particular circumstances. Education quality in this way can therefore only be evaluated at a macro-level aggregating the past outcomes of students.

This information asymmetry falls disproportionately on students. Higher Education providers themselves have inside information about how they resource teaching and the trade-offs they make to achieve a balance between cost and quality. Higher Education providers also have the advantage of large student data sets to evaluate which students are more likely to achieve relative to others.

What a price-signal should achieve

Price-signals naturally reveal information by the participants in order for markets to be self-regulating. A price-signal should resolve problems of uncertainty and information asymmetry through the communication of collective behaviour. Critically for markets in higher education, the price-signal needs to resolve the problem of asymmetric information between Higher Education providers and students with regards to quality.

An effective price-signal in higher education should lead to choices that optimize trade-offs between the price of education (fees) and quality (future earnings). A price-signal has failed if participants in the market make choices where the investment in education is greater than the expected returns.

For normal markets the price-signal is simply the price of a good reflecting the competing forces of supply and demand in the market. However, a higher education price-signal needs also to reflect the likelihood a student’s income-contingent loan will be repaid. Higher Education course fees are not an appropriate price signal for an efficient and effective economic outcomes. Any deregulation of Higher Education fees needs to incorporate a mechanism which allows the market to communicate naturally (incentive compatible) price-signal linked to the expected value of student liabilities.

For markets in debt the price-signal is the ‘yield to maturity’ on the debt – a discount rate on the nominal value of debt reflecting the time value of money (interest rates) and the risk of default (credit risk). For high education, the contingent loan liability arising from Higher Education fees represents the nominal value of the debt and the key price-signal is expiry-risk given that the student loan liability is indexed.

Alternative solutions and why they won’t work

Capping student places: a student centric non-financial constraint that requires students to compete for Higher Education places. Focuses student quality entering Higher Education and not on student quality exiting Higher Education . Competition between Higher Education providers is weak leading to lower diversity and quality differentiation. The objective of capping student places is to keep budgetary impacts within a prescribed limit and relying on assortative rationing to maintain quality.

Uncapping student places with fixed fees: Weak student and Higher Education provider competition leading to significantly lower diversity and quality. Lack of financial and non-financial constraints leading to sub-optimal price/quality trade-offs. Results in significant adverse impact on budget due to no limit on demand.

Uncapping student places with flexible fees: Income-contingent loans remove student wealth constraints leading to sub-optimal price/quality trade-offs for those students that do choose to attend Higher Education . A greater adverse impact on budget due to any (small) reduction in demand more than offset by cost of higher fees due to price inelasticity of education.

Uncapping student places, flexible fees but capped student liability: In theory should provide the necessary financial constraint to drive optimal price/quality trade-offs but maybe be difficult to administer. However, a flexible fee regime would require real-time information flow between Australian Tax Office and Higher Education providers to ensure limits were not breached. Reduced impact on Federal budget burden would be offset by significantly higher transaction costs associated with real-time information. More viable under a system of fixed fees.

Uncapping student places, flexible fees with ‘high fee taxes’: In theory should limit the incentives for Higher Education providers to charge higher fees. In practice however, the price-inelasticity of education will mean any increase in fee price due to a tax ‘surcharge’ will have little impact on demand. Education is considered a “Veblen good’, where price is a proxy for quality and status, taxes will have little impact. An analogy is the imposition of a luxury car tax. Higher taxes actually increase demand not reduce demand in the absence of wealth constraints. Consequently, ‘high fee taxes’ will not constrain fee prices nor improve the problem of optimizing price/quality trade-offs in Higher Education provider choice.

An Incentive Compatible Model for Higher Education deregulation

The key mechanism of this model is to create an ‘incentive compatible’ nexus between the credit risk of student loans and quality at the Higher Education provider level while maintaining the social equity benefits of student income-contingent loans. This is achieved by Higher Education providers selling a pool of income-contingent loan debt to capital markets (fund managers) which are repaid via government tax collection.

The amount of debt funding that a Higher Education provider will be able to raise will be dependent upon the quality of the student loans. ‘Quality’ being measured by the likelihood the loan will be repaid in full which in itself is dependent upon the level of fees charged and the quality of the educational experience.

Critically, the two market participants best able to resolve the problems of uncertainty and information asymmetry, fund managers and Higher Education providers, bear most of the risk. Fund managers having the resources and expertise to price risk under uncertainty and Higher Education providers the inside knowledge to resolve issues of information asymmetry.

This market design leads to more efficient price discovery and optimal economic outcomes via an appropriate price-signal – expiry risk. Differences between market cost of funds, for example the 10 year bond rate, and the rate at which the loan liability is indexed can be subsidized by the government in the form of a tax payment premium to fund managers.

Importantly this model combines the social equity benefits of Income-contingent Loans with a market design that is ‘incentive compatible’ through an appropriate price discovery mechanism. ‘Incentive compatibility’ ensures that the right price-signal and financial constraints lead to economically optimal trade-offs between the price of education (fees) and quality (future earnings). Higher Education providers in return for bearing the expiry risk for student loans, gain the flexibility of setting fee levels and creating course offerings.

Model Design

There are four main agents in the model: Higher Education providers, students, government & capital markets (e.g. fund managers). There are no changes to the fundamental mechanism of income-contingent loans for students. Students will bear no greater risk than they currently incur. The key social objectives of income-contingent loans remain intact. It is important to note that from the student’s perspective, the socially optimal real interest rate for indexing student liabilities is zero (discount rate for intergenerational investments as per Robert Solow, Kenneth Arrow)

The fundamental change is that Higher Education providers will receive student fee revenue from fund managers in exchange for the future payments arising from the student loan liability generated. Fund managers will pay the Higher Education provider the nominal value of the loan liability less an amount to cover the expiry risk of some of the loans not being repaid. Higher Education providers thereby bear the risks associated with the level of fees charged and the quality of education delivered.

Funds are raised via specific pools of student loan liabilities segregated by Higher Education provider. Real-time market pricing of each Higher Education provider fund by unit holders provides the pricing for the issuance of new student loan funds to a Higher Education provider.

The Federal government is able to achieve various social and economic objectives via specific subsidies

- Equity (such as SES or gender) is addressed through tax credits applied directly to student’s loan liability. Early payment of loan liability via tax credits makes these groups attractive to fund managers.

- Economic priority areas for education (such as STEM) are targeted via a cost of delivery payments to Higher Education providers. This subsidy is important to avoid over-supply of low cost courses.

- Socially preferable index rate achieved by adding a cost-of-funds premium to tax receipt payments to fund managers. This allows student loan balances to be indexed at the socially preferable rate (real interest rate = zero) while ensuring fund managers receive an appropriate interest rate on loan funds, such as the 10yr bond rate.

- Counter-balance business cycles by adding a modifier that increases returns during recessions and thereby increasing the attractiveness of funding in times when training is critical to transforming the economy (e.g. a co-efficient linked to unemployment rates).

Issues and Policy Risks

There are a number of risks that are associated with this model:

- Course selection skew – at the margin only as addressed by specific prioritized course subsidies.

- Ability selection skew – at the margin only ( not necessarily a bad outcome given opportunism currently occurring in Higher Education market).

- Gender selection skew – Life history impacts an inherent problem of higher education financing options, principally addressed by income-contingent loans having a real rate of interest = zero.

- Policy implementation risk – this is a major reform and entails a significant amount of risk associated with implementation.

This funding model will most likely lead to both market consolidation and specialisation of some HE providers.